GPIB is a standard bus used in laboratory and industry data acquisition and experimental control that is now available for Linux.

Gambling is a way of life with computers. The technology is changing daily, and anyone involved with system administration should try to keep up with it at any cost. Sometimes it’s all too much. You are asked whether a new feature can be introduced into the network. If you say no, you might fall behind the competition; if you say yes, you’re bluffing and you might be shooting yourself in the foot. Linux became my most loved operating system, when I realized that saying yes is usually more gambling with a good chance of success, than bluffing with an empty hand. My involvement in GPIB for Linux is such a case.

GPIB? What does it stand for?

GPIB is a standard bus in data acquisition and industrial process control. It was developed in 1965 by Hewlett-Packard and was first called HPIB. It was subsequently renamed GPIB (general purpose interface bus) or the IEEE488 interface. GPIB hardware is available everywhere. All kinds of AD converters, digital meters, even printers and plotters use it as the bus of choice. Clean up those dusty corners in laboratories, and you may find an ancient piece of hardware with a GPIB interface at the back. As PCs arrived on researchers’ desks, GPIB interface boards were developed, enabling control of GPIB hardware chains via a computer.

How Linux Support Came to Be

I am involved with the Laboratory for Technical Physics in the Faculty for Mechanical Engineering in Ljubljana, capital of Slovenia. The staff uses GPIB for experimental control and data acquisition, and any computing environment introduced into the lab must support GPIB if at all possible. After I converted the laboratory to Linux, an end was put to printing via floppy disks and waiting in queues for the daily mail on the single computer hooked to the Internet. Standard Linux applications replaced most of the everyday software previously in use. However, GPIB support soon became an issue. I was not really a GPIB freak myself, but I knew about its wide use, and I knew the spirit of Linux from my long-time experience with it. The dice were rolling as I assured everyone, “GPIB for Linux? Yes, of course!” All I had in hand at the time was a short note in the Linux Hardware HOW-TO, directing me to the Linux Lab Project in Germany (see Resources).

Software on the Web

On one fine web surfing day, I found what I needed: The Linux GPIB package, written by Claus Schroter at Freie Universitet, Berlin. The package includes a loadable GPIB driver module, the basic library for accessing the bus functions from C and a Tcl interface, enabling GPIB for the Tcl language.

I had Slackware 3.1, with kernel version 2.0.0 on a 100MHz Pentium board with 16MB RAM. The GPIB interface card available was the CEC PC488. A rather low-end ISA board but good enough for my testing purposes. Informative documentation of the package states that the following boards are supported: National Instruments AT-GPIB, NI PCII and PCIIa and compatible boards, IBM GPIB adapter, HP82355 and HP27109 adapters.

The module and GPIB library compiled out of the box, and after actually reading the README file, Tcl support compiled as well. The driver module can be configured at compile time, at module load time or via library calls. Necessary parameters are the hardware address of the GPIB board, the DMA channel and the IRQ being used.

Before use, the library must be configured as well using the /etc/gpib.conf file by default. A specific configuration can be done for every hardware device attached to the bus. A special identifier name should be provided for each device so that the library can access any hardware device by a reasonable name. I found this method of configuration very convenient. All GPIB devices on the bus have different addresses and their initialization strings vary. With configuration via /etc/gpib.conf file, the necessary parameters must be determined and written into the configuration file only once. Then, all you need to do is remember the arbitrary name you assigned to that device. There is also a Tcl/Tk-based application called ibconf which simplifies maintaining the configuration file.

The feature that drew most of my attention was remote GPIB, rGPIB. It is a very cool option that enables computers without a GPIB board to access a GPIB board on a remote computer across a TCP/IP network. It is much cheaper than buying interface cards and much simpler than swapping one GPIB board between computers. Remote GPIB uses RPC (remote procedure calls) for communication between client and server, so the RPC portmapper must be up and running before the rGPIB server can be used.

What To Do Now

With the package compiled and ready to use, I took a low-frequency spectral analyzer HP3582A with GPIB interface and a HP3312A function generator to feed the analyzer. For readers who aren’t familiar with these machines, imagine yourselves counting the flow of traffic on the highway. The highway represents the function generator. You count the vehicles, determine the increase of traffic from the last count and type the results into a portable computer. With these actions, you act as an analyzer—give or take a few Fourier transforms. That’s the basic idea.

The computer should bring the analyzer up with initialization strings sent over GPIB and set it into a mode, such that all its functions can be controlled via the bus. With this control established, the computer must ask the analyzer for data, and then listen as the data is transmitted to the bus. As it is not my goal to discuss the philosophy of GPIB in this article, it should be enough to note that the GPIB software interface must provide the means of writing and reading strings to and from the bus, plus some extra functions for status and event-driven operation.

I attached the hardware to the Linux workstation and realized that strings could now be transmitted flawlessly in both directions. My work was done, and other members of the laboratory could now use the new setup for serious experimentation. However, as a Tcl/Tk fan, I couldn’t stop at this point—I had to check out the promised Tcl capabilities. A shared library, loadable from Tcl is provided. It adds the new command gpib to Tcl interpreter and all the bus functions can be accessed via the new command.

Somebody Stop Me, Please!

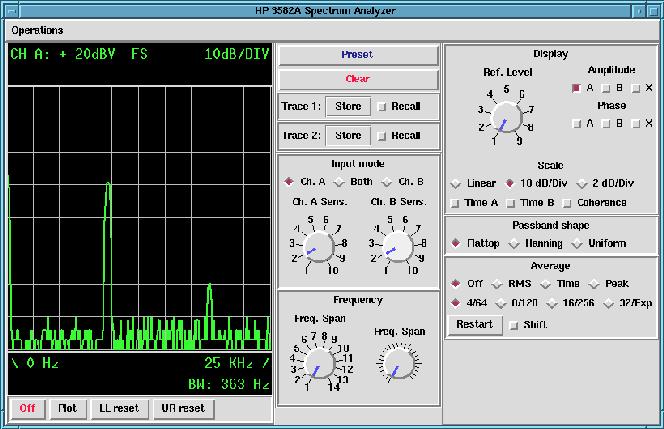

The bluffing worked out one hundred percent, and I held four aces in one hand and a full house in another. Stop? No way! It occurred to me that I could create a user-friendly interface to the HP3582A spectral analyzer using Tcl/Tk power.

I started working on the user interface, then decided to do my own Tcl interface library. Not because anything was wrong with the existing one, I just needed an extra flag to disable actual calls to the GPIB library, because I was doing part of the program development at home without either a GPIB board or network access to a remote GPIB. I added a flag at the Tcl level to enable all of the functions to operate without actually calling the low-level library. With the manual for the spectral analyzer and Linux as the development platform, I created a neat user interface for remote analyzer operation (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. User Interface for Remote Analyzer

What Was This All About?

When I finally recovered from the programming spasm, I pulled away from the keyboard and took time to reconsider the improvement in the laboratory situation. Previously the laboratory had one ancient Motorola-based HP 300 workstation as the main work horse for experimental control. Programming was tedious because most work was done via device file without any high level library. Our other choice was a PC with MS-DOS, which is a fine machine for experimental work, but to my thinking useless as a good development platform. I feel the new solution using Linux workstations is superior to either of the other choices. You can read daily e-mail, work on a GPIB application and perform non-critical measurement at the same time on a single computer. If you are not scared of writing few lines of C code, hacking a script or two and merging together different development tools, a Linux workstation with GPIB support is a splendid machine for an experimentalist. It was my first involvement in GPIB, but the neatness and freedom of the environment raised my enthusiasm and pushed me beyond my original intentions.

There is, of course, the fact that at the time of writing most of the commercially available software for experimental control is native to Microsoft-based platforms or proprietary Unix workstations. But this is changing with Linux gaining ever more acceptance in products for measurement and control. In large environments, where vendor support is an important issue, commercial packages still prevail. However, for universities and research laboratories with enthusiastic staff and less critical demands, the Linux solution is worth trying. Of course, if you are on a tight budget, you don’t have much choice. Linux and the GPIB package are free of charge and usually do not require new hardware. Linux might even save you a bill or two in the future on network-based capabilities. With real-time Linux being introduced to the laboratory now and in the future, there should be no restrictions on the seriousness and the importance of the experiment.

Linux, Linux OS, Free Linux Operating System, Linux India Linux, Linux OS,Free Linux Operating System,Linux India supports Linux users in India, Free Software on Linux OS, Linux India helps to growth Linux OS in India

Linux, Linux OS, Free Linux Operating System, Linux India Linux, Linux OS,Free Linux Operating System,Linux India supports Linux users in India, Free Software on Linux OS, Linux India helps to growth Linux OS in India