Ogg Vorbis is the Open-Source Community’s hot alternative to MP3.

Audio has become one of the killer apps of the network. With the distribution power that the global network offers, the music industry is being reshaped forever.

The boom of audio applications and files on the Internet is responsible for much current litigation surrounding copyright law and music licensing. The record industry is just now figuring out what most early users knew the first time they played an audio file on their computer: it’s a new world for artists, listeners and record labels.

At the center of the upheaval are the technologies that make it all possible and a new technology, Ogg Vorbis, is ready to put this revolution into an even higher gear.

Ogg Vorbis is an open-source and patent-free audio codec that is being developed by Xiphophorus along with several other multimedia projects (cdparanoia and Icecast, to name two). Xiphophorus is a collection of open-source, multimedia-related projects and programmers who are working to ensure that Internet multimedia standards reside in the public domain where they belong. The work on Ogg Vorbis is currently funded by iCAST, the entertainment arm of CMGI.

Ogg Vorbis is an open standard, and this is important for a number of reasons. There are few truly open standards in the realm of digital audio. Look at Windows Media, Quicktime or RealAudio. These standards are all closed and proprietary, and because of this, none of the standards interoperate well (or at all outside of their corporate walls) with one another. When was the last time that you could play Quicktime 4 in RealPlayer or vice versa? When will Linux have Quicktime or Windows Media support? Linux and the Internet are founded on open standards, and as multimedia on the Internet and on Linux rapidly matures, the need for multimedia applications like Ogg Vorbis grows rapidly as well.

There are two parts to Ogg Vorbis: Ogg and Vorbis. Ogg is a wrapper format, similar in some ways to Apple’s Quicktime or Microsoft’s Active Streaming Format. It helps you collect a group of things that belong together. For example, if you have an Ogg movie file, it might contain a Vorbis stream alongside a video stream in another codec. Or the Ogg movie file might contain ten Vorbis streams, one for each language available.

Vorbis is a codec that is written inside the Ogg framework. It is a general-purpose audio codec that is suitable for compressing most audio sources with good results. It doesn’t use subbanding like some codecs do, but it does use vector quantization similar to others.

Vorbis is the only codec we’ve written so far, but not the only one we plan to write. There also are Squish and Tarkin.

Squish is a lossless audio codec, meaning that there is no loss in quality at all, and in fact, the decoded stream would be byte-for-byte identical with the original stream. You might want to use this for archiving master copies.

Tarkin is our fledgling video codec. It’s a work in progress, but I can tell you it’s based on wavelets, not on the MDCT like most modern codecs including MPEG-4 and JPEG. We’re still playing around with it, but it’s quite promising.

Codecs are hard to develop. They take a lot of math skills and a lot of time. Once you finish development, you still have to tune it, fix bugs and think of cool new things to add. This is why Ogg Vorbis focuses primarily on Vorbis and the Ogg framework at this point.

What’s Wrong with MP3?

A lot of readers are probably wondering why we’d bother to develop Ogg Vorbis with MP3 already enjoying such widespread use. What’s wrong with MP3? It’s free, right? Wrong.

Have you ever noticed the amazing lack of free MP3 encoders, especially considering how popular MP3 has become? I can count them all on one hand. Some people will remember the famous letter from Fraunhofer back in late 1997. The letter asked for all the open-source and free MP3 encoders to cease and desist or start paying patent royalties. There are around 12 patents on the algorithms used by MP3, and all of them are heavily enforced by the owner Fraunhofer.

This patent enforcement has several negative effects. It’s nearly impossible to have a free MP3 encoder because of the licensing fees for doing so. It costs $2.50 per download ($5 if you use the Fraunhofer code). Most of the free encoders disappeared without a way to pay this kind of tribute. MusicMatch, which makes a popular Windows encoder, sold a significant percentage of its company to Fraunhofer in exchange for an unlimited license.

Fraunhofer can change their rules at anytime, too. Prior to 1997, distributing MP3 encoders was fine. Right now, broadcasting in the MP3 format is free, but Fraunhofer stated that he intends to charge licensing fees for such use at the end of this year.

The deals the RIAA cuts for the broadcasting of commercial music are typically one-third to one-half a penny per song, which is quite reasonable considering that Fraunhofer may want to charge you 1% of revenue with a minimum of a full penny per song (these are my extrapolations from the current fees on commercial MP3 downloads). Is MP3 really worth three times more than the music it delivers?

It costs $.50 a copy to license a decoder. These aren’t the only costs associated with MP3, and really, some are just my speculations (hopefully the real fee for broadcasting will be considerably lower), but the patent holders can set or change the licensing fees to whatever they want, anytime they want. And, they already stated that they intend to do so at the end of this year for broadcasting. The point isn’t whether it’s $15,000 or $5. The point is they have the right to set the price however they see fit.

MP3 is an old technology. Audiophiles and programmers have been tuning encoders for a long time, but the technology is not improving anymore. Even LAME, one of the best MP3 encoders around, has new options that break the specification to try to squeeze more quality out. There just isn’t anymore room in the format for new tweaks or improvements.

The alternatives aren’t great either. Advanced Audio Coding (AAC), which is a part of MPEG-4, has quite a bit more IP restriction than MP3. There’s more than one company involved in most of the technologies, which makes licensing even more cumbersome. The VQF format is locked up tightly by NTT and Yamaha. RealNetworks and Microsoft aren’t known for their open standards either. Several derivative codecs like MP+ are problematic because they face the same patent restrictions that the regular MP3 codec has.

With all of these inherent problems and the need for a better way to work with audio on the Internet, it’s not surprising that a solution would come from the Open-Source Community.

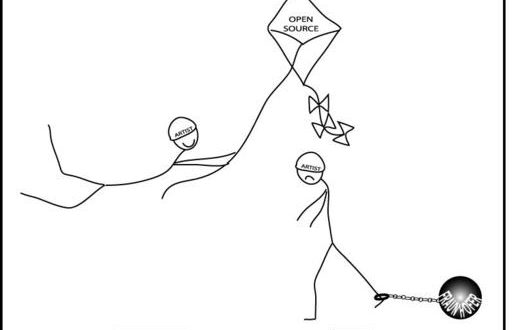

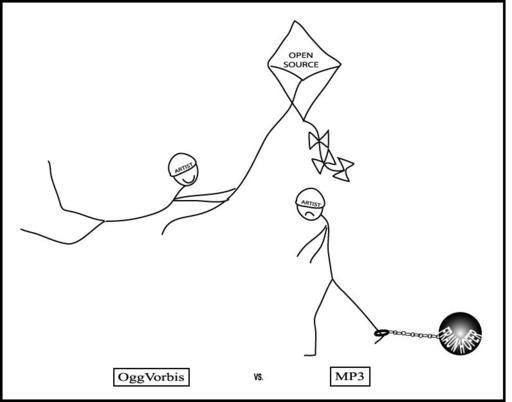

Ogg Vorbis vs. MP3

Figure 1. Ogg Vorbis vs. MP3

Ogg Vorbis is patent free and it was designed that way from the beginning. There are no licensing fees or costs associated with using the format for any purpose whether it is commercial or noncommercial. It’s also open source under terms of the LGPL, so even the source code is free for companies and fellow hackers.

It’s not enough just to be free. Vorbis has superior sound quality, which is what one would expect from a next-generation audio codec. Due to an extendable format, Vorbis’ quality will improve for years to come without affecting decoders already being used. Vorbis sounds great now, but the quality is nothing compared to the Vorbis that will be around six months from now.

Quality is not the only advantage that Vorbis offers. Vorbis has some unique technical features as well: extensible comments, bitrate peeling and access to the raw codec packets.

Comments are defined in the format, so there are no worries about ugly and limiting hacks like ID3 tagging. The comments are stored in name=value pairs, and while there is a standard set of comments for applications to comply with for often-used data, you can add arbitrary comments if you need to.

Bitrate peeling allows for lowering the bitrate of a stream or file on the fly without re-encoding. This is achieved by encoding the most useful data toward the beginning of a packet. Slimming the stream is simply a matter of chopping the tails off of every packet before you send them out. Imagine listening to a radio stream that changes the bitrate based on your personal bandwidth needs. If you have dropouts, it sends you a smaller stream; if your download finishes, it sends you more data.

For multicast or other special applications, access to raw Vorbis packets allows complete control over how data is organized and shuffled around.

And, there’s no reason to put up with leading or trailing silence since Vorbis has sample granularity on seek and decode. Remember all those gaps between tracks on your favorite trance CD? They disappear with Vorbis. Need to seek exactly to sample 303054? Vorbis provides a mechanism to do this. This makes Vorbis well suited to production work in ways that MP3 never was.

Developers and users, will appreciate having a high-quality set of reference libraries. This means that not everyone who wants to write an audio player needs to write their own decoder. Developers also have more time to spend on other things besides audio formats. This allows them to build more sophisticated and useful software.

Current Status

Two and a half years of Vorbis development (most of it as a side project) finally brought us the Ogg Vorbis beta1 release in mid-June of this year. It was limited to one bitrate, but it already had plug-ins for most players as well as support on many platforms.

In August, Ogg Vorbis beta2 release was launched at LinuxWorld Expo in San Jose, California. Five bitrates from 128kbps to 350KBps and several quality improvements were the main features.

Right now we’re rapidly approaching the beta3 release, which has a number of significant quality improvements. This is mostly due to the many pairs of ears that report artifacts and bugs. The code has been organized toward the goal of a permanent API, and several new tools have been added.

Several optimizations were made that resulted in the decoder being twice as fast. We’ve also tuned the code to be tolerant for those who implement Vorbis using integer-only math. This allows hardware and embedded devices to more easily support Ogg Vorbis playback.

We’ve had over 100,000 downloads of Ogg Vorbis in the three months since its release, and third-party support has been wonderful so far. Xmms, Freeamp and Kmpg already support Vorbis playback (even popular Windows players like Sonique and Winamp support Vorbis). LAME can now produce Ogg Vorbis files as well as MP3 files and can re-encode MP3s to Vorbis in one step. Several people reported success with Grip the CD ripper, and new applications are popping up all the time.

A few content producers who are early adopters have started to embrace the format as well. Vorbisonic.com and eFolkmusic.com have Ogg Vorbis files up for download, and you can find more sites listed on the www.vorbis.com pages.

Shortly after our beta1 release, we did some random searches for domain names with “vorbis” in them that showed that a lot of people were buying Vorbis-related domain names. Several Vorbis-related sites have already turned up, including govorbis.com and vorbiszone.com.

Where We Are Going

We have only started the optimization process. On the decoding side, Ogg Vorbis is nearly as fast as the current MP3 decoders and should catch up soon. Several people already claim good playback on Pentium 120 machines. On the encoding side, real-time encoding is already possible on fast Pentium IIs and Pentium IIIs. Now that the API is getting stable and more features are getting knocked out, more and more people have started to turn to the issues of speed.

Comparing Vorbis to MP3 is almost unfair, since Vorbis has no channel coupling, but we’re still ahead. There are some tricky patents that we must navigate, but the development team is looking to Ambisonics to fill this gap. Ambisonics was patented, but the patents have since expired. The company itself went out of business due to stiff competition from Dolby. Ambisonics technology would provide Vorbis with true three-dimensional, spherical sound, which can be mapped onto any number of speakers—all this in only four channels (one and two for stereo, three for surround and four for spherical sound). Taking advantage of channel coupling should easily drop bitrates by 40 percent.

Streaming is also very high on the list. We are currently testing streaming and should have a few test stations up before November. Soon after, Icecast should begin supporting Vorbis as its primary format for audio. This gives Internet radio fans higher quality streams, and it offers broadcasters a way out of end-of-year broadcasting royalties.

For streaming, lower bitrates are vital. Right now the lowest bitrate that the reference encoder outputs is approximately 128KBps. Typical streams range from 24KBps to 64KBps, and we’ll soon focus on the tuning necessary to make low bitrate Vorbis sound fantastic. Lower sample rates are also on the horizon.

And, as always, we rigorously tune and improve the audio quality by adding quality-enhancing features and eliminating noticeable artifacts.

Ogg Vorbis 1.0, which includes the features outlined above, should be completed by the time you read this.

Gaining Ground on MP3

A lot of people ask us how we plan to take over the ground MP3 has already claimed. Some people don’t even think that it’s possible. I think it is. You can’t really compare Vorbis to other audio codecs that have tried to accomplish what we have, because no other audio codec other than Vorbis is more free and more open than MP3. Part of the reason that the MP3 movement succeeded was due to the massive amounts of software that supported it. The software support happened because there was code lying around all over the Internet and documentation on how to use it or to write your own. Some people compare MP3 versus Vorbis to VHS versus Betamax. They say that just because we’re technically superior doesn’t that mean we will win. I guess those people don’t realize that VHS won because the technology was actually more open.

Our strategy is to go after two groups: the artists and the developers.

Artists, and other content producers need, Vorbis to avoid paying percentages of their revenue to some technology company in Germany. Most of these people are also interested in having the best sounding quality product that they can get. People won’t choose Vorbis or MP3 files simply for the sake of technology. People want music from artists they appreciate, or shows on topics they like, and they want the music to be available, transferable and easy to manipulate.

Developers want to include audio in their software—and not just for decoding and playback. Rich-media creation tools are only possible in the open-source world with open-media standards and patent-free algorithms like Ogg Vorbis. Including Vorbis into software is easy (it takes little time for a programmer to write a playback plug-in even if they are new to Vorbis and the Vorbis plug-in API).

If there is content being produced in Vorbis and applications all support Vorbis, the user probably won’t even notice. Ease of use is achieved with transparency. Years from now, we might still be calling on-line music “MP3” just as some people still call making photocopies “Xeroxing”, but the technology will come from different sources.

How You Can Help

Just like any open-source project, Vorbis reaches its full potential only with the help of the community. Programmers, audiophiles, musicians and evangelists are all needed. Encode some music with Vorbis, listen to Vorbis files and let us know if you hear anything that isn’t in the original. Artifacts, once someone identifies them, are usually easily fixed. If you currently have a project that could (or does) play or encode audio, try Vorbis. Not only will the audience for Vorbis grow, but users will appreciate the functionality that Vorbis offers. Instead of creating music and putting it on-line in MP3, do it in Vorbis. By producing Vorbis files, you avoid limitations that patent holders enforce, and you increase user demand for Vorbis. Tell your friends, family and coworkers about Vorbis. Any effort to promote open standards like Vorbis for Internet audio is time well spent. And at this infant stage in Vorbis’ life, we could really use the help.

Conclusion

Open standards for Internet multimedia are a worthwhile and attainable goal, especially with a high-quality open-source audio codec such as Vorbis.

Just as HTTP, FTP, TCP/IP and other open standards helped change the landscape for networking, our goal is to change the face of multimedia with tools that sound better, look better and work together better than the closed or patent-encumbered alternatives. You most likely use an operating system that relies on open standards and open source at its very core; why not expect the same from the multimedia applications you use?

Please visit the Ogg Vorbis demonstration site at www.vorbis.com or the Xiphophorus developers site at www.xiph.org.

Linux, Linux OS, Free Linux Operating System, Linux India Linux, Linux OS,Free Linux Operating System,Linux India supports Linux users in India, Free Software on Linux OS, Linux India helps to growth Linux OS in India

Linux, Linux OS, Free Linux Operating System, Linux India Linux, Linux OS,Free Linux Operating System,Linux India supports Linux users in India, Free Software on Linux OS, Linux India helps to growth Linux OS in India