When you need to network your Linux box with Windows, Samba is the way to do it.

The whole point of networking is to allow computers to easily share information. Sharing information with other Linux boxes, or any UNIX host, is easy—tools such as FTP and NFS are readily available and frequently set up easily “out of the box”. Unfortunately, even the most die-hard Linux fanatic has to admit the operating system most of the PCs in the world are running is one of the various types of Windows. Unless you use your Linux box in a particularly isolated environment, you will almost certainly need to exchange information with machines running Windows. Assuming you’re not planning on moving all of your files using floppy disks, the tool you need is Samba.

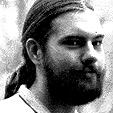

Samba is a suite of programs that gives your Linux box the ability to speak SMB (Server Message Block). SMB is the protocol used to implement file sharing and printer services between computers running OS/2, Windows NT, Windows 95 and Windows for Workgroups. The protocol is analogous to a combination of NFS (Network File System), lpd (the standard UNIX printer server) and a distributed authentication framework such as NIS or Kerberos. If you are familiar with Netatalk, Samba does for Windows what Netatalk does for the Macintosh. While running the Samba server programs, your Linux box appears in the “Network Neighborhood” as if it were just another Windows machine. Users of Windows machines can “log into” your Linux server and, depending on the rights they are granted, copy files to and from parts of the UNIX file system, submit print jobs and even send you WinPopup messages. If you use your Linux box in an environment that consists almost completely of Windows NT and Windows 95 machines, Samba is an invaluable tool.

Figure 1. The Network Neighborhood, Showing the Samba Server

Samba also has the ability to do things that normally require the Windows NT Server to act as a WINS server and process “network logons” from Windows 95 machines. A PAM module derived from Samba code allows you to authenticate UNIX logins using a Windows NT Server. A current Samba project seeks to reverse engineer the proprietary Windows NT domain-controller protocol and re-implement it as a component of Samba. This code, while still very experimental, can already successfully process a logon request from a Windows NT Workstation computer. It shouldn’t be long before it will act as a full-fledged Primary Domain Controller (PDC), storing user account information and establishing trust relationships with other NT domains. Best of all, Samba is freely available under the GNU public license, just as Linux is. In many environments the Windows NT Server is required only to provide file services, printer spools and access control to a collection of Windows 95 machines. The combination of Linux and Samba provides a powerful low-cost alternative to the typical Microsoft solution.

Windows Networking

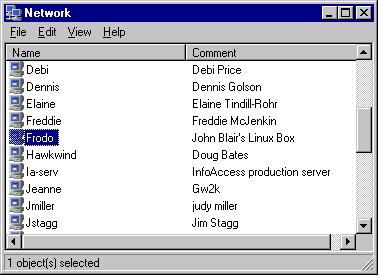

Understanding how Samba does its job is easier if you know a little about how Windows networking works. Windows clients use file and printer resources on a server by transmitting “Server Message Block” over a NetBIOS session. NetBIOS was originally developed by IBM to define a networking interface for software running on MS-DOS or PC-DOS. It defines a set of networking services and the software interface for accessing those services, but does not specify the actual protocol used to move bits on the network.

Three major flavors of NetBIOS have emerged since it was first implemented, each differing in the transport protocol used. The original implementation was referred to as NetBEUI (NetBIOS Extended User Interface), which is a low-overhead transport protocol designed for single segment networks. NetBIOS over IPX, the protocol used by Novell, is also popular. Samba uses NetBIOS over TCP/IP, which has multiple advantages.

TCP/IP is already implemented on every operating system worth its salt, so it has been relatively easy to port Samba to virtually every flavor of UNIX, as well as OS/2, VMS, AmigaOS, Apple’s Rhapsody (which is really NextSTEP) and (amazingly) mainframe operating systems like CMS. Samba is also used in embedded systems, such as stand-alone printer servers and Whistle’s InterJet Internet appliance. Using TCP/IP also means that Samba fits in nicely on large TCP/IP networks, such as the Internet. Recognizing these advantages, Microsoft has renamed the combination of SMB and NetBIOS over TCP/IP the Common Internet Filesystem (CIFS). Microsoft is currently working to have CIFS accepted as an Internet standard for file transfer.

Figure 2. SMB’s Network View compared to OSI Networking Reference Model

Samba’s Components

A Samba server actually consists of two server programs: smbd and nmbd. smbd is the core of Samba. It establishes sessions, authenticates clients and provides access to the file system and printers. nmbd implements the “network browser”. Its role is to advertise the services that the Samba server has to offer. nmbd causes the Samba server to appear in the “Network Neighborhood” of Windows NT and Windows 95 machines and allows users to browse the list of available resources. It would be possible to run a Samba server without nmbd, but users would need to know ahead of time the NetBIOS name of the server and the resource on it they wish to access. nmbd implements the Microsoft network browser protocol, which means it participates in browser elections (sometimes called “browser wars”), and can act as a master or back-up browser. nmbd can also function as a WINS (Windows Internet Name Service) server, which is necessary if your network spans more than one TCP/IP subnet.

Samba also includes a collection of other tools. smbclient is an SMB client with a shell-based user interface, similar to FTP, that allows you to copy files to and from other SMB servers, as well as allowing you to access SMB printer resources and send WinPopup messages. For users of Linux, there is also an SMB file system that allows you to attach a directory shared from a Windows machine into your Linux file system. smbtar is a shell script that uses smbclient to store a remote Windows file share to, or restore a Windows file share from a standard UNIX tar file.

The testparm command, which parses and describes the contents of your smb.conf file, is particularly useful since it provides an easy way to detect configuration mistakes. Other commands are used to administer Samba’s encrypted password file, configure alternate character sets for international use and diagnose problems.

Configuring Samba

As usual, the best way to explain what a program can do is to show some examples. For two reasons, these examples assume that you already have Samba installed. First, explaining how to build and install Samba would be enough material for an article of its own. Second, since Samba is available as Red Hat and Debian packages shortly after each new stable release is announced, installation under Linux is a snap. Further, most “base” installations of popular distributions already automatically install Samba.

Before Samba version 1.9.18 it was necessary to compile Samba yourself if you wished to use encrypted password authentication. This was true because Samba used a DES library to implement encryption, making it technically classified as a munition by the U.S. government. Binary versions of Samba with encrypted password support could not be legally exported from the United States, which led mirror sites to avoid distributing pre-compiled copies of Samba with encryption enabled. Starting with version 1.9.18, Samba uses a modified DES algorithm not subject to export restrictions. Now the only reason to build Samba yourself is if you like to test the latest alpha releases or you wish to build Samba with non-standard features.

Since SMB is a large and complex protocol, configuring Samba can be daunting. Over 170 different configuration options can appear in the smb.conf file, Samba’s configuration file. In spite of this, have no fear. Like nearly all aspects of UNIX, it is pretty easy to get a simple configuration up and running. You can then refine this configuration over time as you learn the function of each parameter. Last, the latest version of Samba, when this article was written in late January, was 1.9.18p1. It is possible that the behavior of some of these options will have changed by the time this is printed. As usual, the documentation included with the Samba distribution (especially the README file) is the definitive source of information.

The smb.conf file is stored by the Red Hat and Debian distributions in the /etc directory. If you have built Samba yourself and haven’t modified any of the installation paths, it is probably stored in /usr/local/samba/lib/smb.conf. All of the programs in the Samba suite read this one file, which is structured like a Windows *.INI file, for configuration information. Each section in the file begins with a name surrounded by square brackets and either the name of a service or one of the special sections: [global], [homes] or [printers].

Each configuration parameter is either a global parameter, which means it controls something that affects the entire server, or a service parameter, which means it controls something specific to each service. The [global] section is used to set all the global configuration options, as well as the default service settings. The [homes] section is a special service section dynamically mapped to each user’s home directory. The [printers] section provides an easy way to share every printer defined in the system’s printcap file.

A Simple Configuration

The following smb.conf file describes a simple and useful Samba configuration that makes every user’s home directory on my Linux box available over the network.

[global]

netbios name = FRODO

workgroup = UAB-TUCC

server string = John Blair's Linux Box

security = user

printing = lprng

[homes]

comment = Home Directory

browseable = no

read only = no

The settings in the [global] section set the name of the host, the workgroup of the host and the string that appears next to the host in the browse list. The security parameter tells Samba to use “user level” security. SMB has two modes of security: share, which associates passwords with specific resources, and user, which assigns access rights to specific users. There isn’t enough space here to describe the subtleties of the two modes, but in nearly every case you will want to use user-level security.

The printing command describes the local printing system type, which tells Samba exactly how to submit print jobs, display the print queue, delete print jobs and other operations. If your printing system is one that Samba doesn’t already know how to use, you can specify the commands to invoke for each print operation.

Since no encryption mode is specified, Samba will default to using plaintext password authentication to verify every connection using the standard UNIX password utilities. Remember, if your Linux distributions uses PAM, the PAM configuration must be modified to allow Samba to authenticate against the password database. The Red Hat package handles this automatically. Obviously, in many situations, using plaintext authentication is foolish. Configuring Samba to support encrypted passwords is outside the scope of this article, but is not difficult. See the file ENCRYPTION.txt in the /docs directory of the Samba distribution for details.

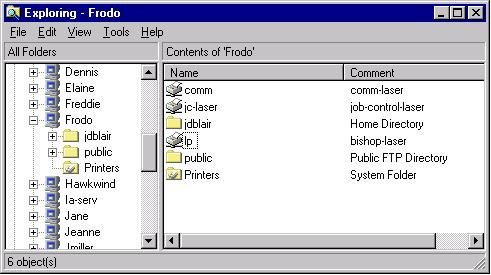

The settings in the [homes] section control the behavior of each user’s home directory share. The comment parameter sets the string that appears next to the resource in the browse list. The browseable parameter controls whether or not a service will appear in the browse list. Something non-intuitive about the [homes] section is that setting browseable = no still means that a user’s home directory will appear as a directory with its name set to the authenticated user’s username. For example, with browseable = no, when I browse this Samba server I will see a share called jdblair. If browseable = yes, both a share called homes and jdblair would appear in the browse list. Setting read only = no means that users should be able to write to their home directory if they are properly authenticated. They would not, however, be able to write to their home directory if the UNIX access rights on their home directory prevented them from doing so. Setting read only = yes would mean that the user would not be able to write to their home directory regardless of the actual UNIX permissions.

The following configuration section would grant access to every printer that appears in the printcap file to any user that can log into the Samba server. Note that the guest ok = yes normally doesn’t grant access to every user when the server is using user-level security. Every print service must define printable = yes.

[printers]

browseable = no

guest ok = yes

printable = yes

This last configuration snippet adds a server share called public that grants read-only access to the anonymous ftp directory. You will have to set up the printer driver on the client machine. You can use the printer name and printer driver commands to automate the process of setting up the printer client on Windows 95 and Windows NT clients.

[public]

comment = Public FTP Directory

path = /home/ftp/pub

browseable = yes

read only = yes

guest ok = yes

Figure 3. Appearance of Samba Configuration in Windows Explorer

Be aware that this description doesn’t explain some subtle issues, such as the difference between user and share level security and other authentication issues. It also barely scratches the surface of what Samba can do. On the other hand, it’s a good example of how easy it can be to create a simple but working smb.conf file.

Conclusions

Samba is the tool of choice for bridging the gap between UNIX and Windows systems. This article discussed using Samba on Linux in particular, but it is also an excellent tool for providing access to more traditional UNIX systems like Sun and RS/6000 servers. Further, Samba exemplifies the best features of free software, especially when compared to commercial offerings. Samba is powerful, well supported and under continuous active improvement by the Samba Team.

Linux, Linux OS, Free Linux Operating System, Linux India Linux, Linux OS,Free Linux Operating System,Linux India supports Linux users in India, Free Software on Linux OS, Linux India helps to growth Linux OS in India

Linux, Linux OS, Free Linux Operating System, Linux India Linux, Linux OS,Free Linux Operating System,Linux India supports Linux users in India, Free Software on Linux OS, Linux India helps to growth Linux OS in India