Armed with Linux and open-source tools, you can even keep an ISP secure.

As an ISP, we are the most vulnerable to attack because of the open nature of our networks. Unlike corporate networks, which can limit access, and can backtrack users, we have to continuously monitor for attacks and, more importantly, successful intrusions. We use several open-source security tools to monitor for intrusions and system compromises. These tools have alerted us to attack and allowed us to quickly respond to intrusions from system compromises.

Introduction

System administrators are known to be trained paranoids. They are not only concerned about updating their systems against the latest program vulnerability, hacking tools and kiddie scripts, but they have to be vigilant against the security holes and exploits that are not known or documented. Most good system administrators can protect their systems against low-level crackers by using standard system hardening techniques (“Post-Installation Security Procedures”, Linux Journal, December 1999). It is the holes that are not known, and the knowledgeable cracker that poses the much greater danger.

Intrusion detection and recovery is a goal of all system security. It usually involves looking for system compromises: checking logs for unusual activity, unusual connections, and alterations in the system files. Of course a system must be secured in order for intrusion detection and recovery to be effective. System administrators would be working double time if they kept finding people breaking into their systems and had to recover from them.

There are many open-source tools available to system administrators to aid in this process.

Intrusion Detection

We use Tiger, Logcheck and Tripwire in cron jobs to continuously monitor the system for incursions and intrusions. They alert us to attacks on our system and allow us to quickly respond to the attack or limit the damage. We also use other security programs, but to allow this article to be manageable, we shall concentrate on programs with stable releases.

tiger-2.2.4

Tiger is a set of scripts that search a system for weaknesses which could allow an unauthorized user to change system configurations, gain root access, or change important system files. System administrators may remember Tiger as the successor to COPS (Computer Oracle and Password System).

Tiger was originally developed at Texas A&M University and can be downloaded from net.tamu.edu/pub/security/TAMU. There are currently several versions of Tiger available: tiger-2.2.3p1, the latest Tiger with updated check_devs and check_rhost scripts; tiger-2.2.3p1-ASC, tiger-2.2.3p1 with contributions from the Arctic Regional Supercomputer Center; tiger-2.2.4p1, tiger-2.2.3 with Linux support; and, TARA, Tiger Analytical Research Assistant, an upgrade to tiger-2.2.3 from Advanced Research Corporation.

Tiger scans the system for cron, inetd, passwd, files permissions, aliases and PATH variables to see if they can be used to gain root access. It checks for system vulnerabilities in inetd, host equivalents and PATH to determine if a user can gain remote access to the system. It also uses digital signatures, using MD5, to determine if key system binaries have been altered.

Tiger is made up of scripts which may be run together or individually. This allows system administrators to determine the best strategy for checking their system depending on system size and configuration. The Tiger script files are available for download at ftp.linuxjournal.com/pub/lj/listings/issue78.

Tiger can be used as an interactive process, or configured to run any or all the scripts using the tigerrc file. In addition, a site file must include the locations of files Tiger may use, such as Crack and Reporter. Sample tigerrc and site files are included in the distribution. We usually start with everything turned on in the tigerrc and the site-sample files, and customize which scripts to run after the initial audit. Tiger can be run by typing ./tiger in the Tiger directory. Using Tiger as an interactive operation will run the Tiger scripts without regard to the amount of time it takes to complete.

The individual checks can be spread out over time using the tigercron script without cluttering up your crontab file. Tigercron uses the cronrc file to schedule the tiger scripts in a manner similar to crontab. Tigercron is a little bit different from the conventional crontab process in that tigercron is run in crontab every hour, and then tigercron, using cronrc in the tiger directory, determines which scripts to run. One advantage of tigercron is it is configured to e-mail a security report only if there is a change from the previous scan. This prevents cluttering the system administrator’s e-mail with status information and creates a red flag for the sys admin that the system has changed and to take notice of a possible intruder whenever a Tiger e-mail is generated.

Tiger outputs a security report upon completion. The output is detailed and prefixed by cryptic error messages. Fortunately, Tiger comes with a utility to explain error messages, called tigexp. A explanation of each error message can be obtained by running tigexp -f <report filename>.

Tiger 2.2.4 has been updated to run with Red Hat Linux using a 2.0.35 kernel. This is great for people who use Red Hat 5.1 and have not upgraded. Systems using other flavors of Linux, or those that have been upgraded will have to update their binary signature file by using the util/mksig script. This allows Tiger binary checks to be updated as new programs are upgraded or installed.

Tiger is an important part of our system integrity monitors. It is proactive in checking for ways root can be compromised and scans for changes in important system files. In the past, we have been alerted to system intrusions because of Tiger.

Logcheck 1.1.1

Logcheck is a script that scans system log files and checks for unusual activity and attacks. This assumes that an intruder has not gained root privileges to a host and cannot alter the log files. One of the big problems with keeping good log files is a lot of information gets collected. Manually scanning log files could take days on large systems. Logcheck streamlines the task of system log monitoring by categorizing the logged information and e-mailing it to the system administrator. Logcheck can be configured to report only the information you want to see and to ignore all information you don’t want to see. Logcheck can be downloaded from www.psionic.com/tools/logcheck-1.1.1.tar.gz. It is part of the Abacus Project, an Intrusion Prevention System, however, not all the other components are at stable releases yet. Logcheck is based on a log-checking program called frequentcheck.sh, part of the Gauntlet Firewall Package.

The logcheck.sh script is installed into /usr/local/etc/ along with the keyword files. The script can be downloaded at ftp.linuxjournal.com/pub/lj/listings/issue78.

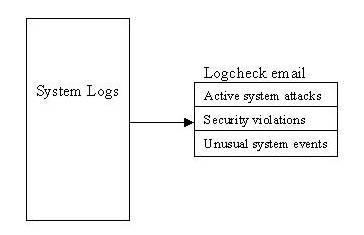

Logcheck scans the log files for active system attacks first, then security violations, and then unusual system events. Logcheck then e-mails a report to root (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Logcheck Operation

In this sample Logcheck e-mail, I purposely logged on to my system from a host that was not allowed to connect, and then used some common hacking probe commands on my sendmail port. Logcheck detected the attempt to gather userids using sendmail and listed it as an “Active System Attack Alert”. It found that a user ftp’ed on to the system in the “Security Violations” section; they may have misspelled their legitimate user ID, or may be a cracker probing the system for user IDs. It also found system trying to connect to us that is not allowed to connect.

Finally, in the “Unusual System Events”, anything out of the ordinary that is not specifically ignored is shown. Logcheck creates a .offset file to mark the portions of logs it has scanned to avoid repeating information it has previously processed.

Logcheck is based on the assumption that syslog is configured to log as much information as possible, and, if possible, to log all activity to one file for easier parsing. Parsing only one file ensures that information will not be missed. We logged all our information to /var/log/messages in addition to the standard log files. This requires more disk space, but it makes debugging system problems easier. Logcheck is heavily biased toward Firewall Toolkit and BSDish messages from TCP wrapper. Systems not using Firewall Toolkit or TCP wrappers may need to add keywords for their security/monitoring programs.

Logcheck is useful only to help administrators spot attacks and take precautionary measures, but once a intruder gains access to your system, one of their first steps will be to hide their tracks by disabling logging.

We use Logcheck as a tool to monitor attacks on our system, intrusion activity and system problems. We pay specific attention to individual attacks on our system and cross reference older Logcheck outputs to try to establish patterns of probing and attacks that occur over weeks or months. The distributed or time-spaced probing of our system is considered high-priority because it usually shows a determined or organized attacker with the patience to look for, and take advantage of, new exploits and program holes. We run logcheck in cron daily, and change to an hourly check if we suspect active probing or attacks.

Tripwire

One of the best-known and most useful tools in intrusion detection and recovery is Tripwire. Tripwire creates a signature database of the files on a system, and when run in compare mode, will alert system administrators to changes in the file system. Tripwire is different from Tiger in that it is a dedicated file signature program, which can use multiple hash functions to generate digital signatures.

Tripwire was developed for the Computer Operations Audit and Security Technology (COAST) laboratory at Purdue University. The publicly available version, Tripwire version 1.2, is available from www.cs.purdue.edu/coast/archives Tripwire version 1.2-2 is shipped with Red Hat on the powertools CD as RPMs and is also available from ftp://ftp.redhat.com/pub/redhat/powertools/. Tripwire has been available as a commercial product since January 1999 from Tripwire Inc. Tripwire 1.3 is distributed as an Academic Source release. 2.x.x versions are available in binary-only form. Both can be downloaded from www.tripwire.com/downloads/index.cfmlfor noncommercial use. Tripwire Inc. has announced it will be adopting an open-source model for Tripwire by the third quarter of 2000, but has not yet settled on a licensing scheme.

A great many articles about Tripwire exist, so we will concentrate on using Tripwire as an intrusion detection tool rather than how to use Tripwire.

As I mentioned before, when an intruder penetrates a system, one of the first things they will try to do is hide themselves and their activities from the system. In order to accomplish this, they will commonly substitute system files with Trojan horse binaries—binaries with code added to them—which filter their activities. Common Trojan binaries are TELNET, login, su, FTP, ls, netstat, ifconfig, du, ps, inetd and syslogd. Intruders will also try to create back doors for themselves by adding a user to passwd or a service to inetd. In most cases, they will try to take the /etc/passwd file and run Crack on it hoping to find users with weak passwords.

Intruders will also install tools to allow them to monitor the network or maintain access to a system. They will try to install programs with known vulnerabilities to allow them to gain root access, often in “hidden” files. They may also install network scanners, and probes to collect information and possibly passwords from network traffic sent in clear text.

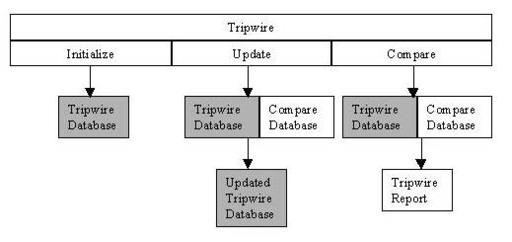

Figure 2. Tripwire Operation

Tripwire as an intrusion-detection tool requires a pristine image database of the system, a snapshot of your system in a known uncompromised state. The best scenario (see Figure 2) is to be able to take a clean snapshot or “fingerprint” when the system is first installed. As programs are installed and upgraded, the system administrator compares the new file signatures to make sure only the programs they worked on are updated to the database and that no other system files were altered.

Capturing the digital signature of the entire file system can create an information overload for the system administrator. Parts of the file system are supposed to be changed with normal operations, so capturing the files in /var/spool, /tmp, or even /var/log can be useless because they are constantly being altered. At the same time, we need to be able to identify files hidden in the system if we detect a compromise. To accomplish the different need of the scans, we create two Tripwire configuration files with two Tripwire databases: one to scan the entire system and one to scan only critical system files.

System administrators have different opinions as to which files are “critical”. We take the view that system binaries and libraries should not change unless we change them. So all *bin and *lib directories, such as /bin, /sbin, /usr/bin, /usr/sbin, /lib and /usr/lib should be fingerprinted by Tripwire. In addition, all system configuration files in /etc should be fingerprinted. The files and directories to be scanned can be configured using tw.config. We can redirect the config file and database to be used by using the -c and -d switches of Tripwire.

Tripwire can be used as an intrusion-detection tool by having it run comparisons as a cron process. Any system files that were altered without the system administrator’s knowledge would be a sign that the system has been compromised and that immediate action needs to be taken to limit the damage. Clear signs that a system has been compromised are changes to system files involved in login, access privileges, and process monitoring or accounting.

When an intrusion is detected or suspected, Tripwire can give the system administrator an indication of the extent of the damage by identifying the files that have been changed. If an intrusion has been detected early, the cracker may not have had time to penetrate the system, and may have had time only to start the process by bringing over tools and programs. This is where the fingerprint of the full system is valuable. Using a full scan of the system, hidden files and directories can be identified and investigated. Rather than manually scanning the file system for new directories and files, Tripwire will flag them and output them to the Tripwire report.

A knowledgeable cracker, one who knows about intrusion detection, will commonly try to hide programs in the file structure where they knew the system files would be changed during normal operations, thereby hiding themselves from abridged cron Tripwire comparisons. Places where a system adminstrator should pay especial attention is /tmp, /dev and /var/spool directories because files are created and deleted during normal operations. Crackers will try to hide their directories by prefixing them with . (dot), so they do not show in a normal ls command.

File integrity checkers should be a part of every system’s security; Tripwire is the “best of breed” in this area. It can be used as an alarm to a system penetration and in intrusion recovery.

Intrusion Recovery

When an intrusion has been detected, the system administator needs to first regain control of the compromised system by disconnecting it from the network. This is to prevent further intrusion and possible Denial of Service attacks on the Internet originating from the compromised host. An image of the system should be backed up to allow for the intrusion to be analyzed and referenced later.

The system must then be analyzed thoroughly by reviewing log files. This is a primary source of information on how, when and where the intrusion occurred. All system binaries and configuration files, including the kernel, need to be verified to make sure they are unaltered. To do this, the system administrator must first insure the system analysis tools themselves are clean and do not contain Trojans. System data should also be checked to make sure the intruder has not changed them. Intruders may “park” data or programs on the system. This may include programs to be used in other intrusions, and data from other compromised systems. Intruders may also install network sniffers and other monitoring programs in hopes of capturing information which will allow them to access other hosts. Once an intrusion has been detected on one system, all the other systems on the network should also be checked for possible intrusion. The intruder may have used the compromised system to gain access to other hosts on the network, or they may have used other hosts to gain access to the system with the detected intrusion.

System administrators should file an incident report for all hosts compromised with a computer coordination center, such as CERT. Intruders usually use compromised accounts to attack other system. It is difficult or impossible for an individual system to track down the origins of a knowledgeable attacker. However, it is made possible through cooperation among system administrators, closing down avenues of attack and access, limiting the attacker to hosts and systems where they can be monitored and identified.

Once an intrusion has been analyzed and reported, then comes the task of recovering from the intrusion. First a clean version of the system should be installed, preferably from the original installation media. If a backup is used, the system binaries should be restored from copies with known clean binaries. The sys admin should take the paranoid stance that the latest backup may contain the altered programs and data and needs to be sure they are not reinstalling bad files.

Once a compromised system has been restored, it must be secured to prevent another intrusion. Steps in hardening a system include disabling all unnecessary services, installing all vendor security patches, consulting CERT and other security advisories, and changing passwords.

Conclusion

Detecting and recovering from an intrusion may actually be the start of a system administrator’s security journey. Intrusions only highlight the need for system security. With millions of users on the Internet, one has to assume that, while individually they may pose minimal threat, collectively they are more knowledgeable and have more resources than any system administrator or security program.

Bobby S. Wen (wen@vasia.com) holds two engineering degrees and an MBA. He started playing with Linux in 1994 with a Slackware pre-1.0 distribution and has been addicted ever since. Even though he has a computer for every man, woman, child, and dog at home, he still has to wait his turn for a computer, because the only computer his children want to play with is the one he is working on. He currently multi-boots Linux, FreeBSD, Solaris, BeOS, Windows 98 and Windows NT.

Linux, Linux OS, Free Linux Operating System, Linux India Linux, Linux OS,Free Linux Operating System,Linux India supports Linux users in India, Free Software on Linux OS, Linux India helps to growth Linux OS in India

Linux, Linux OS, Free Linux Operating System, Linux India Linux, Linux OS,Free Linux Operating System,Linux India supports Linux users in India, Free Software on Linux OS, Linux India helps to growth Linux OS in India