Linux and ham radio share a common spirit of cooperation, experimentation and do-it-yourself attitude. These two interests come together in packet radio.

In my teens I spent many enjoyable hours tinkering with radio equipment and communicating with other “hams” around the world through the medium of amateur radio. Moving away to attend a university and start a career and family meant that my hobby had to go on temporary hiatus for a number of years. Recently, I came back to the hobby and decided to explore an area of amateur radio that didn’t exist in my teen years—digital packet radio. As an avid Linuxer, I was intrigued to see how I could use my Linux system for packet radio. I was on a limited budget, and wanted to get started without investing in a lot of hardware and software.

What Is Ham Radio?

Amateur radio is a pursuit enjoyed by millions of “hams” around the world. By international agreement, most countries have allocated a portion of the radio spectrum for amateurs to experiment with radio technology. The hobby goes back to the early days of radio and is popular with people of all ages. Operating an amateur radio station requires an operator’s license, which can be obtained by passing an examination that covers radio theory, regulations, operating practices and basic electronics. Full privileges also require a knowledge of the International Morse Code (yes, it is still used) although some countries now offer no-code licenses that typically include restrictions in operating modes and frequencies.

Hams are known for building their own equipment and accessories, experimenting with new technologies and helping each other and the public. This is close to the spirit of Linux, so it is not surprising that many hams are also Linux users.

What is Packet Radio?

As personal computers became increasingly powerful and affordable, amateurs looked at using radio for digital communications. Packet radio is one such method in which text is encoded as binary data and transmitted via radio in groups of data, called packets. One popular protocol developed for this purpose is AX.25. Based on the X.25 protocol but adapted for the special needs of amateur radio, it offers error-free, packet-based communication between stations. Other protocols, such as TCP/IP, can run on top of AX.25. A few of the applications of packet radio include chatting by keyboard with other hams in real-time, using packet bulletin board systems, sending electronic mail, and connecting (via gateways or worm holes) to other packet networks or to the Internet. Data rates range from 300 bits per second on HF (High Frequency) bands to 1200 bps on VHF (Very High Frequency) and 9600 to 56Kbps and beyond on UHF (Ultra High) frequencies.

What Kind of Packet Radio Hardware Do You Need?

A typical packet radio station consists of a computer or terminal connected to a Terminal Node controller (TNC), and radio transceiver (transmitter/receiver). A TNC is a device containing a small microprocessor, dedicated firmware in ROM, and a modem to convert signals back and forth between audio and serial bit formats, and also encodes and decodes data with the AX.25 protocol. A typical TNC connects the radio to the computer via its serial port.

Another popular option is the “poor man’s modem-only” Terminal Unit (TU). It essentially has a modem chip sandwiched between its audio and serial port connectors. Software drivers on the computer must therefore handle all of the AX.25 protocol. It’s popular because of the price—typically one third the cost of a TNC.

The typical DOS-based packet setup has a number of limitations. Since the system is single user, the computer must be dedicated to packet and cannot easily be used for other purposes. Generally, the computer is used as a dumb terminal or dedicated software is used that takes over the whole computer. Although some software packages such as JNOS run on XT or AT class machines, Linux typically runs better on a 386 machine having limited memory than a commercial operating system alternative such as Windows 95.

Packet software is either free or distributed as shareware in binary form. Some packages, notably JNOS, are also available as source code.

What Does Linux Offer?

As of release 2.0, Linux has native support for the AX.25 protocol built into the kernel (a unique feature among operating systems). For earlier releases, Alan Cox’s AX25 package is easily patched in. Furthermore, AX25 is integrated with the rest of the Linux networking code and utilities. To Linux, a packet radio interface appears as just another network interface, much like an Ethernet card or serial PPP link.

The kernel contains device drivers for serial port TNCs as well as several popular packet modem cards. It even offers a driver that uses a sound card as a packet modem (more on that later).

Once up and running, you can let users telnet into your Linux system via packet radio, offer them a Unix shell or one of several BBS programs, or even let them surf your system with a web browser. Thanks to Linux’s multiuser and multitasking capability, this occurs without affecting the normal use of the system.

A Linux machine can act as a router to connect packet network traffic to a LAN or Internet connection and can route e-mail via packet. You can have multiple packet interfaces with many simultaneous connections over each interface.

Back to My Story

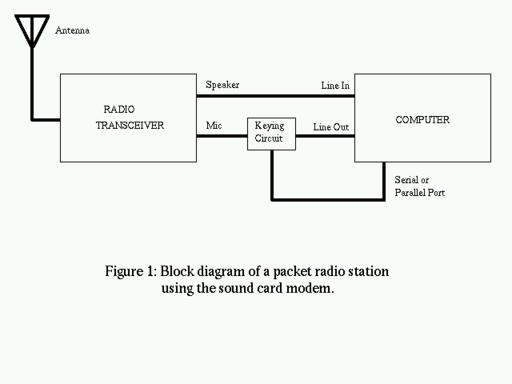

My first introduction to packet was using the sound card modem driver with a hand-held 2-meter band transceiver for 1200bps packet. The audio connects from the PC sound card to the radio’s microphone and speaker jacks. A signal from a serial or parallel port in conjunction with a simple (one transistor) circuit is used to control the radio’s PTT (Press To Talk) circuit. This approach requires no TNC and no packet modem—if you already have a computer and sound card this costs almost nothing. Figure 1 shows a block diagram of my setup.

Configuring the system was straightforward—I just followed the detailed instructions in the AX25 HOWTO. Utility programs included with the AX25 package allow me to monitor the packets being broadcast and received, and to call and answer other packet stations.

I obtained an IP address from the local IP coordinator (the 44.x.x.x ampr.org Internet domain is assigned for packet radio) and configured my system for TCP/IP over packet. All the standard network tools then operated over packet. Assuming they are configured for TCP/IP, I can ping or finger other stations and connect to them using telnet. Similarly, I can log on to my home Linux machine over the Internet.

Next I plan to set up a simple BBS system users can log on to via packet radio. I’d also like to look at more sophisticated packet networking tools supported under Linux, such as NetRom, NOS and Rose. In the future I may even explore options for higher-speed packet such as the 56 Kbps Ottawa PI2 card.

Conclusions

As well as being fun, packet radio under Linux taught me a lot about networking, much of which is also applicable to Ethernet, X.25 and other network protocols.

Linux is a great platform for packet, particularly since it is fully integrated with the rest of the networking subsystem. Its reliability lets you leave a Linux system up for long periods of time without crashing (ideal for a BBS environment). As an example, one local Linux system has been on the air continuously for over 310 days without interruption. Some of the software I used was still in alpha release yet was stable enough to use. Finally, packet radio has opened up a whole new area of Linux for me to explore, ensuring that I won’t run out of things to do in the foreseeable future.

Acknowledgments

Thanks go to Gord Dey, VE3PPE, for reviewing this article and adding many valuable suggestions. I also wish to thank Terry Dawson for writing the AX25 HOWTO and utilities, Alan Cox, Jonathan Naylor and others for writing the Linux packet code and Thomas Sailer for writing the sound card packet modem driver.

Linux, Linux OS, Free Linux Operating System, Linux India Linux, Linux OS,Free Linux Operating System,Linux India supports Linux users in India, Free Software on Linux OS, Linux India helps to growth Linux OS in India

Linux, Linux OS, Free Linux Operating System, Linux India Linux, Linux OS,Free Linux Operating System,Linux India supports Linux users in India, Free Software on Linux OS, Linux India helps to growth Linux OS in India